Run the Ball to Win in the NFL

Run the ball to win. That has been the mantra for years in the NFL. Many players and coaches who have become media members swear by that philosophy. There is even a cliché that states, “pass to score, run to win.” With the number of people throughout the history of the game saying that a commitment to the run wins football games, it would lead people to think it is true. Is it? The answer is right here and it is a solid yes.

The issues with proving or disproving this tactic starts with the box score. Don’t use it. Box score analysts and fans will show you the number of wins when a team runs for 25, 30 or more times in a game, but that is a very small picture of a larger topic. The box score is misleading.

The explosion of football analytics over the past decade has tackled many questions, including if running the football wins games. Many fans have seen something similar to this next graph showing that teams run more when they are winning towards the end of games.

First, this graph only dispels the box score analyst assertion that running more wins. Second, it typically uses a percentage of run vs. pass instead of sheer rushing numbers which will indicate that a good offense tends to win more often than a poor offense. It leaves important pieces of the game out of the analysis.

The reason that many players and coaches talk about winning with the running game is threefold. The more an offense can run the ball, the more it wears down a defense. Being able to run the ball when the defense knows it is coming has a psychological impact on the defense. Finally, running the ball helps the offense set up impactful passing.

The above graph does not address any of those impacts. It simply confirms that when a team is ahead they tend to hand the ball to a running back more in the latter part of a NFL game. That is a no brainer. To truly understand if more carries wins football games, we must not pay as much attention to the fourth quarter.

Rather, we must analyze these questions; 1. Do more rushing attempts in the first half lead to more wins? 2. Do more rushing attempts in the first half lead to more wins when the offense is in balance? And 3. Do more rushing attempts in the first half lead to more wins when in an balanced offense and when the score is within seven points. Furthermore, we must compare this to passing in the first half.

This will normalize score differential, remove the large number of runs when leading late in a game, and remove the differences between effective offenses versus ineffective offenses. It will also lead us to understand if the impact on wearing down a defense physically and psychologically has some relevance.

Using NFL play-by-play data for the past 10 seasons, we can answer all these questions. The next graph indicates the win/loss difference by tracking every rushing play across each second in the first half and depicting those as a moving average line graph. The blue line is the winning team and the black line is the losing team.

When looking at the graphs, if the two lines were overlapping or the black line was above the blue line it would indicate that more rushing attempts doesn’t lead to winning. That is not the case. The blue line separates from the black line almost immediately and they rarely converge except for the start of the second quarter and only four times throughout the half. The blue line, or winning team line, departs significantly from the losing team line by mid-second quarter.

By looking at just the sheer number of runs through the first half, it is apparent that running the ball more leads to winning the game. This occurs without any analysis of the teams with leads in the fourth quarter.

When a balanced offense is added to the mix, the result becomes even more evident. The next graph adds in a more balanced rushing to passing ratio by only including offenses that had a rushing percentage between 45% and 65%.

Again, the blue line, or winning team line, separates right away and remains distant from the black line, or losing team line. This indicates that an efficient offense that runs more wins more often. A good offense that is dedicated to the run is usually victorious.

The next step is to remove large leads. The following graphs adds one more element, the score. It must be within seven points throughout the first half.

Again, running more indicates a greater likelihood of winning, even when the score is close. An emphasis on running the ball with large leads are removed in this part of the analysis and the result is still the same. Running the ball wins.

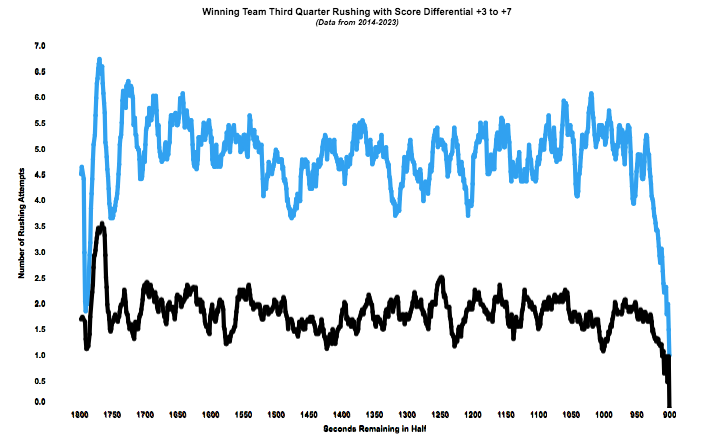

The final point of emphasis is to look at the third quarter only. The next graph illustrates how running the ball more in the third quarter leads to winning when a team is ahead by only one score. By looking at the data presented in these graphs, it is difficult to deny that running the ball more leads to winning football games.

The next question is, does passing the ball more lead to the same result? Below depicts the number of passes in the first half in the same way as we depicted the number of rushes. The winning and losing team lines are very close together and converge multiple times. This indicates that passing more doesn’t have a similar impact as running the ball. Passing more in the first half does not lead to wins as often.

The conclusion is that running the football more, positively impacts a team’s ability to win games. The more a team hands the ball to a running back, the greater the chance of victory, even in the pass-happy NFL of today.